Alberto Burri – Childhood and Education

Alberto Burri was born in 1915 in Città di Castello, Perugia in the Umbria region of Italy. His father, Pietro, was a wine merchant and his mother, Carolina, was an elementary school teacher. From an early age, Burri demonstrated a passion for drawing and a desire to understand the works of the great Renaissance masters, and especially Piero della Francesca, whom he admired above all others. He also studied geometry and Greek, a language in which he became fluent. He continuing to read classical Greek literature throughout his life.

Between 1934 and 1939, Burri trained at the University of Perugia, specialising in tropical medicine and graduating as a doctor in1940, shortly before Italy entered the Second World War. He volunteered for the Italo-Ethiopian war, and then in October 1940, he was called up for frontline service as a combat medic, serving in campaigns in the Balkans, Ethiopia and Libya. Even though he was a man of few words, it is known that the effects of war, and especially the death of his younger brother Vittorio on the Russian front in 1943, left him with deep psychological scars.

Early Training

On 8 May 1943, Burri’s unit in Tunisia was captured by the British. Once turned over to the Americans, he was transported to a prisoner-of-war camp in Hereford, Texas, which housed some 3000 Italian officers. Among his fellow prisoners were academics, architects, and the artist Dino Gambetti, founder of the Sintesi group. It was Gambetti who encouraged Burri to take up art as his chosen leisure activity as offered by the YMCA. He said later, “I painted every day […] it was a way of not having to think about the war and everything around me”. Restricted in his access to arts materials, Burri made use of objects he found in the camp including sackcloth and recycled industrial and commercial canvas. He was a resourceful man who, when he ran out of white paint turned to toothpaste, for instance. Among his early works were views of the desert captured from behind the wire fences that contained him and his compatriots.

Following his repatriation in February 1946, Burri, prompted by his musician cousin, set up a studio in Rome. This went against the wishes of his parents who urged him to practice medicine and paint as a pastime (“I will not be a Sunday painter”, he protested). Burri created figurative paintings through thick chromatic marks and, having made contact with institutions that were dedicated to reviving the visual arts after the war, his first solo exhibition took place at Galleria La Margherita in Rome during July 1947. His move into abstraction burgeoned following a visit to Paris where he was inspired by the tar-paper collages of Joan Miró and Jean Dubuffet’s paintings on coarse bitumen backgrounds. During this period Burri also showed works with the Rome Art Club where he was exposed to arte polimaterica (multi-media art).

Milton Gendel, the American critic, described Burri as “a funny character”. He was a reserved, solitary and intensely private person who rarely gave interviews or socialized with other artists. Details of his life are thus limited to the progression of his work dating from the late 1940s. Between 1948 and 1950, he continued experimenting with unorthodox materials such as tar, sand, zinc, pumice, Aluminium dust and Polyvinyl chloride glue. In 1948 he produced Nero 1 (Black 1); for the artist himself, a career milestone and the first in a series of important monochrome works.

For his first collection of 1949, Burri employed a jute sack; a lasting memento of his incarceration. Burri himself emphatically rejected the idea, put by several commentators, that his Sacchi (Sacks) were a metaphor for violated flesh, with the stitching representing the surgeon’s art of suture: “In reality, there is no relation whatsoever between my work as a doctor and my work as an artist,” he insisted, “I never had, as some have hypothesized and written, flashbacks of any kind about gauze, blood, wounds or other stuff”. The Curator Natasha Kurchanova observed indeed that “Burri’s awareness of the dominant currents in contemporary art led to a visible transformation in materials themselves and in the way he used them, despite the fact that the focus on the physicality of the painting’s support [remained the] constant throughout the artist’s career. In the immediate postwar period”, she continued, “his art reflected the strong influence of Jean Dubuffet and art brut in the use of raw or shapeless materials, such as tar, pumice stone or burlap bags whose unformed and uncontrolled quality was manifest in the work”.

Taking inspiration from the mixed-media abstractions of Enrico Prampolini, Burri developed his Catrami(Tars) series in which he used tar both as a base and as a color. Evaluating his Catrami for the Guggenheim, curator Emily Braun argues that though “there are no figurative images or descriptive realism in his work”, Burri still ranks as a realist because his work “intends the realism of facts – factual materials, things in the real world that he brings together and puts before our eyes”. Indeed, he would also combine sacking and cloth, roughly stitched together against a black or dark red ground, visible through tears and burn holes, creating, in his own words, “a whole chain of pulls and tensions”.

Further explorations of this type followed with materials including bark, linen, corrugated cardboard, sheet and rusty metal, crushed stone, charred wood, and artificial packaging material. These items were often deliberately damaged to endow them with an expressive quality. In his Bianchi (Whites) (1949) series, meanwhile, Burri brought white “into its own”; that is, as a color, a process and as a material. Varying tones, textures and finishes were created with the artist’s fingers, a palette knife, or a trowel on cotton duck, muslin, or linen fabric. The Sacchi and Bianchi pieces started to bring Burri acclaim. His incorporation of a portion of the American flag in SZ1 Sacco di Zucchero (Sack of Sugar 1) (1949) was thought by some to have anticipated Pop Art though, once more, Burri rejected the idea that one should read any social or symbolic meaning into his work (and that somehow the work was a commentary on contemporary America).

As his career developed, Burri’s synthetic approach became more pronounced. The dripped and concreted Muffe (moulds) series resemble bacterial invasion, soil, or mould, with Burri recreating the organic materials by mixing ground pumice stone with paint, mineral particles, and synthetic resins. Thick in relief, the Muffe also suggest aerial views, maps or the dry landscapes familiar to him from time spent in Africa and the Texas Panhandle (though presumably the artist would have rejected such a hypothesis). Retreating for several months to a shepherd’s hut at an isolated spot in the mountains near his hometown of Perugia, Burri began to create his first “swellings” by inserting two small branches between the stretcher and the canvas. In these works, which he called Gobbi (Hunchbacks), Burri was able to distort the picture plane by creating a protruding surface. He developed this technique by replacing the branches with bent metal rods.

Mature Period

By 1950 Burri was making arrays out of burlap sacks and white family cloths. His work was not met with public endorsement in Italy, in any case. He was dismissed by the Venice Biennale in 1952, however his fortunes changed when the organizer behind the Spatialism development, the Argentine-Italian Lucio Fontana, embraced his work by buying the very first piece Burri sold, Studio per lo Strappo (Study for the Rip) (1952).

His arrays began to welcome him acknowledgment on the worldwide stage and Burri held his most memorable independent displays in the United States in 1953 at the Allan Frumkin Gallery, Chicago, and the Stable Gallery, New York. His work likewise highlighted in Younger European Painters: A Selection (1953-54) at the Guggenheim Museum, while his Gobbi series was highlighted in the powerful ARTnews magazine in 1954. Burri’s cozy relationship with the US was solidified when he met Minsa Craig, an American ballet artist and understudy of Martha Graham. They wedded on 15 May 1955 in Westport, Connecticut.

Around a similar time, Burri lit to try different things with fire for of making unique works. His controlled consumed paper works were utilized as outlines for a book of sonnets by Emilio Villa while Burri’s Legni (Woods) series (1955) saw him foster another strategy of scarring birch or oak, which was clasped and mutilated by an oxyacetylene light. In 1957 he proceeded to change the outer layer of plastic with a blowtorch to make a painterly, mark-production procedure which he called Combustioni (Combustions). Kurchanova recommended that the craftsman’s psyche was working and these pieces were the immediate aftereffect of Burri’s encounters of war and his resulting imprisonment. She commented that the series “uncovers that injury continues forever. The roasted, consumed, punctured and generally disregarded bits of plastic were made into painting by an imaginative demonstration of a never prepared in this man calling, yet went to it naturally: there was essentially no greater way for him to survive the apocalypse”.

Likewise in 1957, Burri was subject of a midcareer review at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh by which time his work had drawn in light of a legitimate concern for Robert Rauschenberg. The American made two trips to Burri’s studio in Rome and took motivation from the Italian’s change of tracked down materials into dynamic pieces. The two specialists traded works and, on his get back, Rauschenberg purportedly tossed his very own portion works into the Arno River so he could begin painting over again. It is imagined that Burri had given Rauschenberg the catalyst to start work on his renowned “Joins” series. As far as it matters for him, Burri, who was attached to shooting and hunting, involved Rauschenberg’s fills in as focuses for skeet (dirt pigeon) shooting, naughtily guaranteeing he expected to expand the degree of workmanship in Rauschenberg’s artistic creations.

A progression of reliefs, produced using cold-moved steel called Ferri (Irons), saw Burri cutting and welding his materials. With works like Grande Ferro M5 (1958), Burri changed steel sheets into forcing reliefs by “sewing” his metal planes along with a welding light. Workmanship pundits Enrico Crispolti and Nello Ponente deciphered the Ferri as addressing here and there Burri’s (humankind’s) battle with life yet the craftsman liked to see them as absolutely materialistic. The Ferri, said Burri, were “likewise form. What I have tried to coax out of them is just their property. Iron, for instance, proposed a feeling of hardness, weight, sharpness. I was not keen on addressing iron. The fact that the material was iron makes it immediately understood. I needed rather to make sense of what iron was prepared to do”.

Burri additionally made pieces from softened and singed plastic known as Combustioni plastiche (Plastic ignitions), presenting different materials to various rates of fire from lights and lights. Openings were consumed to open a rich spatial organization inside the layers of plastic. This cross breed of painting and model addressed an exceptionally actual type of innovative obliteration: “He utilized fire to enter material, to go through it and change it. It was a fierce demonstration tantamount to birth”, said one pundit. As a rule, in any case the Italian public was delayed to warm to him. A significant display of Burri’s work at Rome’s Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in 1959 was so disputable – surveys conveyed derogative titles, for example, “Burri Patches a Picture” or “The Doctor-Painter Sticks to Sutures” – it provoked an administration examination. One Italian craftsmanship gatherer responded to the idea that he could buy a Burri with frightfulness: “Painting? Foul sacks! Form! Trash!”.

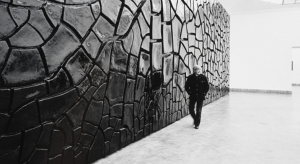

Burri and Craig wintered in Los Angeles consistently between 1963 until 1991. He fostered an interest with the mud pads of Death Valley National Park and was propelled explicitly by the normally cracked floor of the desert. This drove him to make the Cretti (Cracks) series utilizing an exceptional combination of kaolin, tars and shade which he then, at that point, dried the outer layer of the canvas before a broiler. The series, typically painted totally white or dark, featured the sculptural help brought about by the breaking with the outer layer of the works reviewed the coating crumbling of Old Master compositions.

Later Period

Burri additionally made stage sets for La Scala, Milan and different theaters, dealing with plans for plays, artful dance and drama. The most significant of these was Spirituals, Morton Gould’s expressive dance held at La Scala in 1963. Afterward, in 1973, Burri planned sets and outfits for November Steps, a creation imagined by his better half with a score by the Japanese writer Toru Takemitsu. In it, the artists communicated with a film portion of Burri’s Cretti being made. His Plastiche were likewise used to sensational impact in plays like Tristan and Iseult, acted in 1975 at the Teatro Regio in Turin.

Towards the finish of 1970s, Burri highlighted in various reviews, one of which, in 1977-78, advanced across the United States and finished with a presentation at the Guggenheim in New York. Burri’s craft filled in scale too with the 1979 pattern of canvases, Il Viaggio (The Journey), remembering, through ten amazing creations, the critical snapshots of his imaginative turn of events.

In 1985, 27 years after the Sicilian town of Gibellina was decreased to a heap of rubble in a quake, the city chairman of the town welcomed craftsmen and planners to the region fully intent on making memorial establishments. Burri proposed packing the old city’s remaining parts and covering them with iron and concrete. Grande Cretto Bianco (Great White Crack) stretched out over a region of nearly 85,000 square meters making it one of the biggest show-stoppers at any point understood. Really covering the vast majority of the straightened town with white concrete, the breaks between the pieces of cement are adequately huge to stroll between – subsequently making a broad tangled structure. The caretaker Rita Salerno made sense of that the “80 thousand square meters [sic] of white cement and rubbish tells the story of a city cleared off of the world’s guides” and that the “white paths that today can be strolled – similar as profound injuries in the Earth – are the very that were once tracked down in the memorable town before the seismic tremor”.

In the last series of his life, Burri gave proper respect to the enhancements in the basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna. Through the blend of gold and dark, Burri evoked the glass mosaics of the Byzantine landmark. Gold, Burri said, “is the ideal material. In Chinese similar person, jawline, implies both gold and metal. Gold focuses radiant as the light. In India it is called ‘mineral light’. The indication of illumination and outright flawlessness, the pictures of Buddha are made of gold, similarly as the tissue of the pharaohs is gold”. The resultant series, Oro e Nero (Gold and Black), was given to The Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

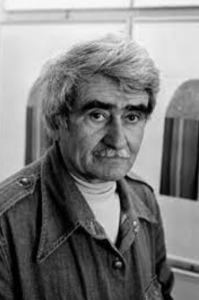

Alberto Burri, shot by Nanda Lanfranco

In 1981, Burri obtained a home in Beaulieu, close to Nice in the south of France. In his last years, he started to utilize Celotex, a modern combination of wood creation scraps and glues, utilized for protection sheets, making works in light of a reasonable mathematical design. As a feature of the establishment he laid out in 1978, Burri planned his own gallery in Città di Castello’s Palazzo Albizzini, which opened in 1981. In 1990 Burri created his last open workmanship when works painted on excoriated fiberboard went on long-lasting showcase in a complex of previous tobacco-drying sheds known as the Ex Seccatoi del Tabacco. Burri passed on February fifteenth, 1995 in Nice.

The Legacy of Alberto Burri

Burri impacted craftsmen of his own time and of later ages. His entrance of the material into three-aspects made ready for the Spatialist slices of Lucio Fontana, while the Arte Povera development took on Burri’s utilization of regular materials, leaving hints of the physical and synthetic changes of nature in their works. Burri’s utilization of fire interfaces him to Yves Klein and the Zero Group while photos of him taking shots at a lager can, and the ensuing presentation of the penetrated can, connect Burri to Niki de Saint Phalle. His craving to change materials likewise reverberated with Joseph Beuys, who met with Burri in Città di Castello in 1980 (Beuys himself had a horrendous encounter during the conflict). Anselm Kiefer’s profoundly finished surfaces, in the interim, consolidate breaks and branches to reflect cultural injury – and absolutely help the watcher to remember Burri (albeit no documentation of formal connection exists).

His commitment to human expressions was recognize in his own lifetime both by Italy and America through, separately, the Legion of Honor and the title Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, and as privileged individual from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The trouble in characterizing Burri as far as the significant patterns in innovation has brought about him being excused by some as “a craftsman of the fringe”. However, most as of late, his permanent commitment to late-20th century deliberation was affirmed through the 2015 significant review presentation Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting arranged by Emily Braun for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and, in the next year, Burri Lo spazio di Materia tra Europa e USA at Città di Castello (his place of birth). The two displays commended the extreme changes in customary Western canvas, arrangement and model started by Burri.

ALBERTO BURRY SUMMARY

Burri was, with Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni, one of the pre-prominent Italian multi-media craftsman of the 20th 100 years. While the American cutting edge was pointed toward “Activity Painting, Burri sought after a more concentrated on way to deal with dynamic craftsmanship. His inclination for unrefined substances, which conveyed the impact by Jean Dubuffet and the Art Brut development, saw Burri join the spaces of painting and help mold. Pundits have been leaned to decipher his course materials as emblematic of his tiresome encounters as a clinical official in the Italian armed force, and, consequently, as a POW. Yet, Burri, who had portrayed himself as a “polymaterialist”, consistently kept up with that his craft was about trial and error and interaction as opposed to individual experience. As his global standing climbed, Burri went to shaded modern materials and he fostered the strategy of “painting with burning”; an interaction by which he made burnt wood facade, welded steel reliefs and organizations of liquefied and roasted plastic. Burri additionally encouraged an interest in broke surfaces which arrived at its high point with his stupendous Grande cretto project; an endeavor that, however just finished after his demise, sits gladly on the Sicilian scene as one of the biggest Land Art works at any point understood.

Achievements

Burri had his initial effect on the post war craftsmanship world through his theoretical Catrami (Tars) series for which he utilized tar pitches both as a base and as a variety (dark). However the works were non-metaphorical, Burri was remarkable among conceptual specialists since he was thought of as a “pragmatist”. He procured this qualification since he utilized genuine, or consistently, materials -, for example, hessian firing, sand and squashed pumice stone – to rejuvenate his coarsely finished materials.

Applying tar-like substances as one would apply impasto oils, Burri looked to investigate what kind of impacts could be accomplished by utilizing a solitary monochrome tone. By glutting and scratching his thick painted surfaces, Burri was really exhuming the exceptionally medium he was working with, showing a manner by which the craftsman could move toward the material for the purpose of obscuring the splitting line among painting and model.

Not at all like other post-war dynamic painters who zeroed in on immediacy and self-articulation, Burri embraced a stringently calculated way to deal with his work. His work was quick to investigate the natural rot and risky annihilation of materials and his designed materials demonstrated so imaginative he made companions of two fundamental American craftsmen Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg, both of whom traded inventive thoughts with the Italian.

Through works, for example, Gobbi, Burri united painting and model, embedding stowed away, however jutting, objects behind the materials for the purpose of upsetting and twisting the two-layered picture surface. His utilization of tracked down objects to make compositions saw him lined up with the strategies for Synthetic Cubism yet Burri’s works went past blend by stretching the actual boundaries of the two-layered surface.

Burri fostered an interest with ignition and fire’s ability to consume materials. Having started by utilizing his fire to “join” metal plates together, Burri immediately turned his oxyacetylene light on to surfaces of wood and plastic. He framed darkened and undulating surfaces that uncovered how the skin of materials surrendered to the damaging power of fire. He had succeeded, consequently, in turning something horrendous (fire) into something imaginative (workmanship).